DC's Iran Conversation Is Stale - and It's One Reason the War Happened

Even the doves sound like hawks.

The Israeli-American war with and upon Iran is a mistake and a tragedy, claiming the lives of many innocent people (including in Israel) for the sake of various deluded geopolitical schemes and personal political calculations. Of course Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, American President Donald Trump, and their teams deserve substantial blame. But I also lay a small but signifiant share of the blame at the feet of editors of leading American publications and the way they have kept “policy conversations” about Iran stale and hawkish for decades. It is true that the hawks have a formidable network of think tanks and media platforms, allowing them to distort the conversation on Iran; it is also true that the hawks receive very little pushback in some of the most important venues in American public debate.

In comparison with the range of possible viewpoints and ideas one might hold, the conversation within the American foreign policy establishment is remarkably narrow - and within that generally narrow space, the conversation about Iran is particularly constrained. You see those constraints in two ways: (1) the ideas and viewpoints that are platformed by major institutions and publications and (2) the voices and authors who are platformed by those venues.

No single essay better illustrates the poverty of the current conversation than an op-ed published on June 24 in the New York Times by former Secretary of State Antony Blinken. Here’s the opening:

The strike on three of Iran’s nuclear facilities by the United States was unwise and unnecessary. Now that it’s done, I very much hope it succeeded.

That’s the paradox for many former officials like me who worked on the Iran nuclear problem during previous administrations. We shared a determination that Iran never be allowed to produce or possess a nuclear weapon. Iran without a nuclear weapon is bad enough: a leading state sponsor of terrorism; a destructive and destabilizing force via its proxies in Lebanon, Syria, Gaza, Yemen and Iraq; an existential threat to Israel. An Iran with a nuclear weapon would feel emboldened to act with even greater impunity in each of those arenas.

This is what passes for disagreement and opposition in official Washington - Blinken endorses Trump’s strikes while offering, in the rest of the op-ed, a complete demonization of Iran and a self-contradictory and revisionist history of even Democratic presidents’ policy on Iran. Blinken tries to both praise President Barack Obama’s 2015 deal with Iran (which was a good thing, one of Obama’s few foreign policy accomplishments) and simultaneously dance around President Joe Biden’s failure, and Blinken’s own failure, to resuscitate that deal after President Donald Trump shredded it. Blinken writes, “The nuclear deal effectively put Iran’s program to make fissile material, the fuel for a nuclear weapon, in a lockbox, with stringent procedures for monitoring the program.” But then somehow he also writes:

Our deployments, deterrence and active defense of Israel when Iran directly attacked it for the first time allowed Israel to degrade Iran’s proxies and its air defenses without a wider war. In so doing, we set the table for Mr. Trump to negotiate the new nuclear deal he pledged years ago to work toward — or to strike. I wish that he had played out the diplomatic hand we left him. Now that the military die has been cast, I can only hope that we inflicted maximum damage — damage that gives the president the leverage he needs to finally deliver the deal he has so far failed to achieve.

For Blinken, Trump has “failed to achieve” a deal in five months, but the Biden administration supposedly succeeded by requiring four years to “set the table” for a deal and piece together a “diplomatic hand” for their successor. Why were Biden and Blinken merely “setting the table” rather than restoring the deal themselves, you ask? As many critics and observers say, the Biden team, out of political cowardice and laziness, shied away from pursuing a deal when they had a chance early on. The cravenness of Biden is what really “set the table” for the recklessness of Trump.

But the point here is not ultimately to re-litigate the deal’s convoluted history over the past decade, but more to say that Blinken’s op-ed epitomizes the problems with Iran discourse in DC and in the quasi-official publications of the American foreign policy establishment (the New York Times, Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy, the blogs and reports of major think tanks, etc.). There are prominent voices who criticize current policy, but their criticisms are so tepid and concede so much rhetorical territory to the hawks that one sometimes feels there are only one-and-a-half viewpoints being aired: “Go to war now” and “not yet.”

Even one of the architects of the 2015 deal (Robert Malley), in a recent Foreign Affairs essay, could only offer a vague lament that the U.S. should have avoided war because the consequences are unpredictable. He and his co-author end by framing Iran and the Middle East as, essentially, savages:

The years that lie ahead will not reflect tidy plans and rigorous policy prescriptions. They will be shaped by instinct and emotion, inspired by raw, deeply-rooted yearnings for historical redress and vengeance. This is not a world built by or for Americans. They will be at sea.

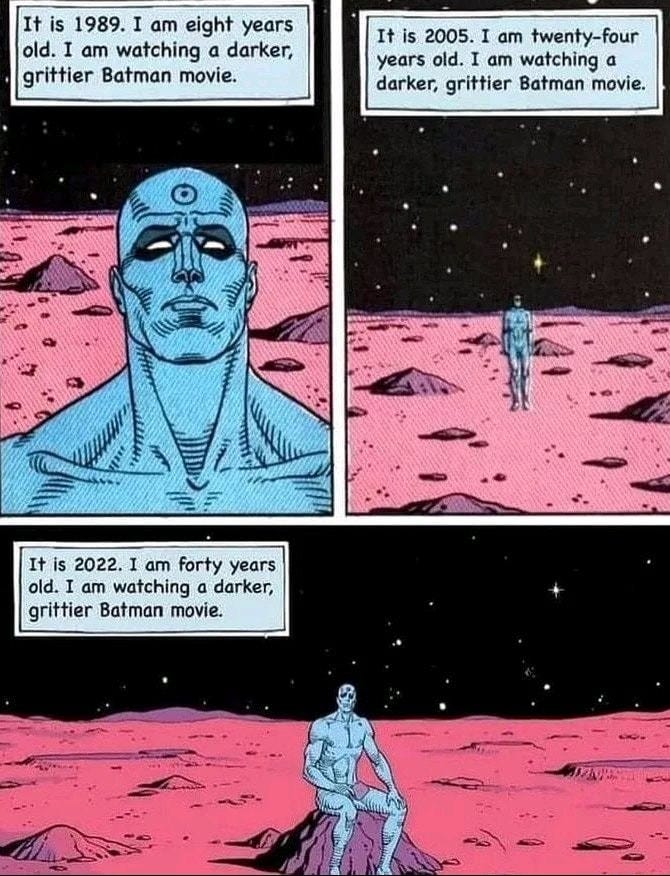

Observing the Iran conversation over the past few weeks has reminded me of the following meme:

Replace all that with: “It is 2005. I am twenty-one years old. The Middle East is in crisis. John Bolton and Rob Malley represent the two poles of ‘legitimate’ debate on Iran…It is is 2025. I am forty-one years old. The Middle East is in crisis. John Bolton and Rob Malley represent the two poles of ‘legitimate’ debate on Iran…”

The new voices who have joined that “debate” in the intervening years have largely adhered to an unofficial but widely followed script. As Ladane Nasseri has underscored with sharp satire, there are recurring stock phrases, images, and assumptions in much U.S. discussion of Iran. In one key bullet point, Nasseri writes:

Unlike the U.S., which wants the best for all the people in the world, Iran wants the worst for the entire universe, itself included. To explain this, always cite comments from the Mullahs, the Revolutionary Guards, the Basij militiamen, all known as the hardliners. Avoid using terms like moderate, centrist, or reformist since all politicians in Iran are wolves, even if some occasionally appear dressed as sheep.

I actually disagree with her slightly here - I think some of the commentators she mocks actually do very deliberately use terms such as “reformist,” but primarily to cast anyone other than the “hardliners” as feckless and untrustworthy.

One could add - I would add - that there has been a swell of sophisticated expertise on Iran that has come into play in the last fifteen years or so. I may have even made that point here on the newsletter before. In academia, scholars such as Narges Bajoghli, Pouya Alimagham, Shirin Saeidi and others have written books and articles offering deeply informed analyses of fundamental aspects of Iranian politics and society. In left-wing publications such as New Left Review and at left-leaning think tanks such as the Center for International Policy, one can read well-informed and insightful analyses of current events by thinkers such as Eskander Sadeghi-Boroujerdi, Negar Mortazavi, and Sina Toossi. All of those researchers have major platforms and their voices are heard to some extent in policy debates. But they are often overshadowed by the spotlight placed on figures such as Blinken.

Here it is worth recalling that Blinken’s vaunted foreign policy expertise is not actually expertise about the workings of other countries, it is about how to be a foreign policy professional within DC and within the U.S. government; Blinken knows a great deal about Iran policy, but I am not sure he knows much about Iran, especially outside the framework of how Washington sees Iran. The same goes for his longtime boss, by the way.

And while one sometimes hears from sophisticated, U.S.-based (or Europe-based) scholars of Iran (many of whom are Iranian by background, and/or do serious fieldwork in Iran), one is much less likely to encounter - in the New York Times, in Foreign Affairs, etc. - perspectives from Iran. One might occasionally see an op-ed from an Iranian president or foreign minister in the pages of a leading American newspaper (see here, for example), but those op-eds are obviously official government statements and are framed as such. What one does not see, in my experience, are American outlets platforming Iranians in Iran who defend or even simply explain the Iranian system and/or Iran’s foreign policy - or who articulate perspectives that humanize Iranians as something other than potential pro-Western revolutionaries. One finds instead fistfuls of articles, especially in the heat of any given crisis, that depict Iran as unremittingly evil. The whole conversation thus ends up shot through with deeply entrenched assumptions that “we” (the U.S. and the “good” Iranians) want Iran to be a certain thing, and that Iran should be punished if it’s not that thing - there may be some debate over how to do the punishing, but there is not much debate over the basic premises of the conversation. Meanwhile, to point out one of the most obvious contradictions, there are many U.S. “allies” and “partners” whose awful human rights records and destabilizing regional postures rival Iran’s, but which are not talked about in the same instrumentalist, punitive way.

The U.S. Left, finally, has some work to do in broadening the conversation about Iran. What are the ideas for U.S. policy towards Iran beyond “don’t go to war” and “bring back the nuclear deal”? What about calling for full diplomatic normalization with Iran? The recent book How Sanctions Work (whose co-authors include the previously mentioned Narges Bajoghli as well as Vali Nasr, who of all the longtime fixtures of the DC Iran conversation has been, in my view, the most constructive and insightful) also provides much ground for thinking beyond sanctions, although I think the book’s tone (for example, the authors write “sanctions…are a tool for creating an enemy that only grows more dangerous and aggressive the longer sanctions stay in place…”) still adheres to the formula of treating Iran as an alien entity. The goal in my view should be to articulate a path towards full-scale peace, a path that does not rely on prolonged coercion or the fantasy of anti-regime uprising.

My favorite example of this was David Frum's headline "Right Move. Wrong Team."

Rather paradoxically, Donald Trump is an outlier in this regard. He's repeatedly made comments about his desire for Iran to be a "rich," "strong," and "successful" country, which don't seem to be referring to a hypothetical post-uprising state but rather the current regime/current state. This is exemplified in policy, I believe he used that rhetoric most recently in reference to his support of renewed oil exports to China. It's absolutely undercut by the bombings he ordered! but is at least a slightly more moderate perspective.