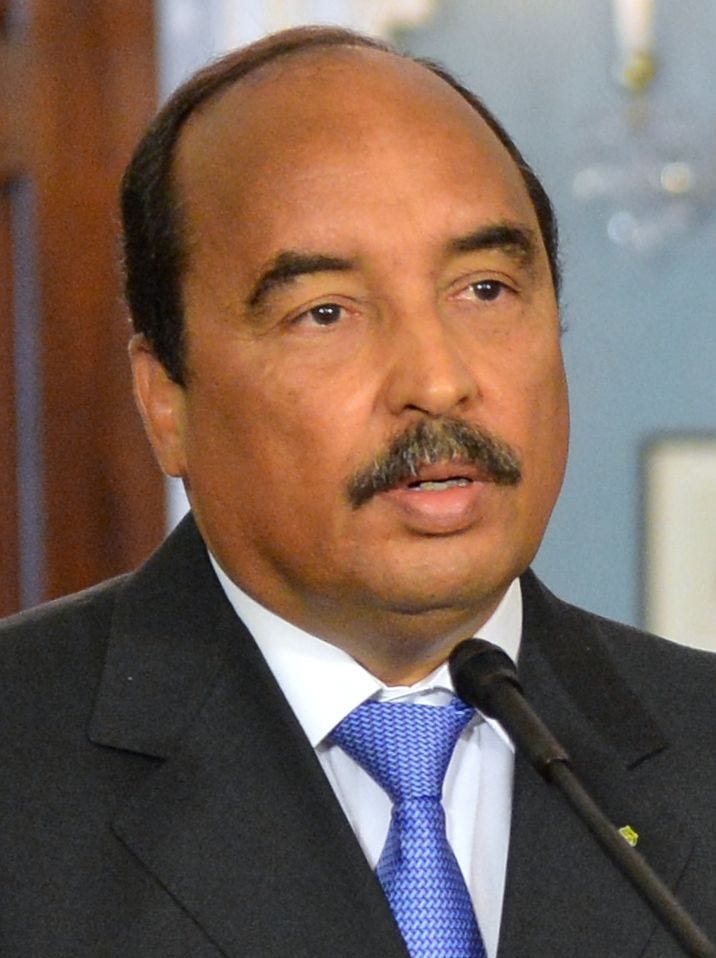

Mauritania: Thoughts on the Prison Sentence for Former President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz

How can authorities crack down on corruption without incentivizing zero-sum politics?

Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz (b. 1956) has been a central figure in Mauritanian politics for more than two decades. Joining the Mauritanian military as a young man, he ascended through the ranks under President Maaouya Ould Sid’Ahmed Taya (in power 1984-2005), eventually becoming commander of the presidential security battalion called BASEP. In 2005, he co-led a coup against Ould al-Taya, and then oversaw a somewhat superficial and shaky transition of power to civilians before staging a second coup in 2008. (These events are the subject of compelling analysis in Noel Foster’s Mauritania: The Struggle for Democracy.) Ould Abdel Aziz then ran for president as a civilian in 2009, won, and ultimately served two terms from 2009-2019. After more or less openly toying with the idea of seeking an extra-constitutional third term, he stepped aside in favor of his longtime military colleague and hand-picked successor Mohamed Ould Ghazouani, who had been another co-leader of the 2005 and 2008 coups. Ould Ghazouani won the presidential elections of 2019 and promptly fell out with Ould Abdel Aziz, especially concerning control of the ruling party, then called Union for the Republic and now called El Insaf (Equity). Ould Ghazouani won that power struggle and a parliamentary investigation soon began probing alleged corruption that occurred during the administration of Ould Abdel Aziz. The investigation triggered Ould Abdel Aziz’s arrest in 2020, followed by a long detention, a conviction in 2024, and now a conviction on appeal just yesterday (May 14). Ould Abdel Aziz has received a fifteen-year prison sentence. Two co-defendants received prison terms as well, including his son-in-law Mohamed Ould Msabou, while another was acquitted.

The political implications of all this are tricky. It is quite plausible to me that substantial corruption occurred under Ould Abdel Aziz. And corruption cases, to have teeth and deterrent force, have to sometimes produce serious convictions and consequences. In my own country, the United States, I’ve often lamented that a lack of accountability - for the administration of George W. Bush, for example, over issues of torture and the launching of the Iraq War - have set the stage for further problems and abuses.

Yet in Mauritania and in many other countries, I suspect, Ould Abdel Aziz’s case will reinforce the image of politics as being zero-sum. Watching Ould Abdel Aziz’s case play out these last five years and more, I had thought that the authorities would stop short of destroying him, personally and politically - I had thought they might keep him in legal limbo, affording him some of the privileges of a former head of state but neutralizing his ability to enter the political arena. I was wrong; this now stands as one of the stiffest legal penalties any former head of state has received, short of the truly dramatic scenarios of execution amid revolution.

Mauritania often flies under the radar, but heads of state in northwest Africa and beyond will certainly be aware of the case and its stark outcome. What incentives will heads of state have to step down voluntarily, if they suspect and fear that prison will be their new home? Picking one’s successor seems like the way to foolproof a transition, and yet it’s often that same successor who might turn on the patron. The military regimes of the central Sahel, or President Alassane Ouattara of Cote d’Ivoire (currently seeking a fourth term in this October’s elections), or President Kais Saied of Tunisia, could all easily conclude from the fate of Ould Abdel Aziz that it’s better to remain in power as long as one can. For that matter, Ould Ghazouani himself might draw that lesson.

Further, heads of state may also take the lesson that they need to destroy their political opponents. What happens, after all, if one doesn’t? Former heads of state are perennially interfering and/or staging comebacks. Ivorian authorities have blocked the candidacy of former President Laurent Gbagbo, but Ouattara might wish that Gbagbo was even more constricted. Or to take another case, if one believes that former Nigerien President Mahamadou Issoufou had a hand in the 2023 coup against his successor Mohamed Bazoum, then perhaps Bazoum (sitting for years now under house arrest) sometimes wishes he would have moved against Issoufou early in the way that Ould Ghazouani appears to have moved against Ould Abdel Aziz. The zero-sum politics can cut both ways - in a fragile institutional environment, if you lash out at your predecessor and your opponents, you look like an autocrat; but if you don’t, they could topple you.

What looks like the ultimate form of accountability and the triumph of institutions over personalities, then - the corruption investigation, I mean - ends up creating many grim incentives for politicians and rulers. I don’t know the way out of that trap; anti-corruption crackdowns is a core political demand of ordinary people around the world, including me. Yet there is no clear way to remove the anti-corruption investigation from its political context. The best case scenario I can think of is that the incumbent, seeing his/her predecessor’s fate, would rein in corruption in the present and think about how to balance accountability with some degree of political pluralism. We’ll see how all this plays out in Mauritania - the next major political crossroads, the 2029 elections and the coming of Ould Ghazouani’s two-term limit, are not actually so far away now.