In Nigeria, nationwide protests are scheduled to begin August 1 (or even as soon as today, according to some reports). The protesters plan to decry the rising cost of living as well as what they see as bad governance - #EndBadGovernance is one key slogan. The protesters draw inspiration from the recent anti-government demonstrations in Kenya, as well as from key protest episodes in Nigeria’s past, particularly (1) the 2012 “Occupy Nigeria” protests against a proposed removal of the fuel subsidy and (2) the 2020 #EndSARS protests, which targeted the Special Anti-Robbery Squad but also focused more broadly on issues of police brutality and elite impunity. There have also been numerous other protests and strikes in the interval, including some already this year.

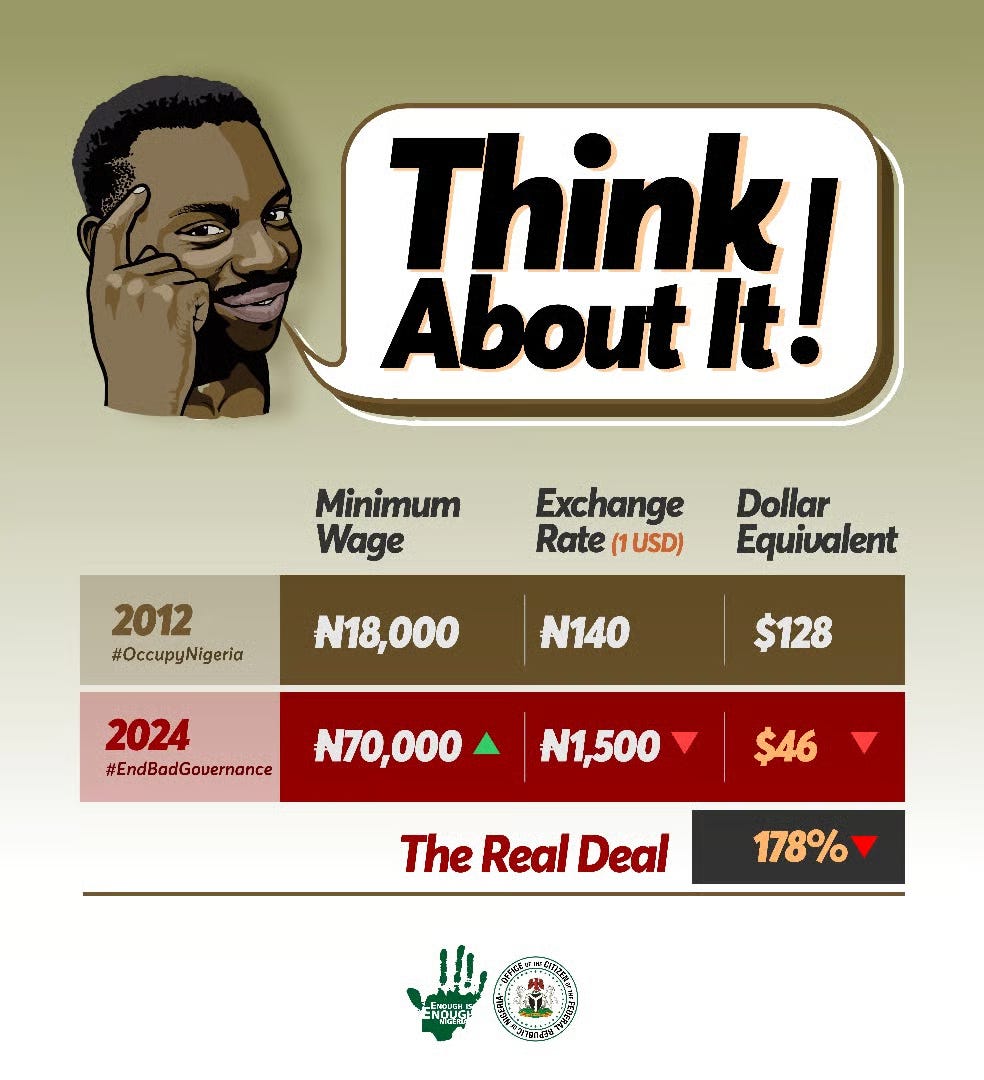

In Nigeria’s tremendously complex political landscape, there are disputes over who makes up the protest coalition, as well as a broad range of views on whether protests will help or harm the country. The Nigeria Labour Congress has said it “cannot withdraw from a protest that it did not organise,” and the National Association of Nigerian Students has distanced itself from the protests. But plenty of groups are claiming leadership roles, for example Enough Is Enough (EIE), a youth advocacy and protest group that formed in 2010. In a post called “Clear Demands, Better Future,” EIE lays out the core issue in the following graphic:

The protests also appear to have a substantially organic character. On TikTok, one can find pro-protest videos with view counts ranging from the low hundreds to over a million. On the whole, the support appears to come broadly from labor, students, and youth, and from multiple parts of the country - a substantial development in one of the world’s most ethnically and religiously diverse countries.

That organic and national character to the movement, I think, is one major factor that has made President Bola Tinubu nervous. Tinubu, a major figure in Nigerian politics since 1999, a former governor of Lagos (1999-2007), and the top architect of the current ruling All Progressives Congress (APC), took office in 2023. He won a remarkably low plurality of the vote in the 2023 elections amid a three-way contest (and several significant minor candidates as well) and a hotly disputed outcome. He inherited a bad economic situation, as did many other current world leaders, but he also played to international investors by removing fuel subsidies and prioritizing stabilization of the naira, Nigeria’s currency (although investors still aren’t happy), whose devaluation has contributed to inflation. The fuel subsidy issue has haunted Nigeria for years, as I alluded to above in mentioning 2012; international financial institutions argue its removal is key to balancing the budget, but the subsidy also made life easier for millions of ordinary people.

Tinubu’s nervousness has shown through in several last-ditch measures meant to stave off protests or at least sap their momentum. These measures include raising the minimum wage, offering new jobs through the state oil company, and revitalizing a grant program for youth. Tinubu’s government has also pleaded with youth for “more time.” Or one could say that the president’s messaging has been contradictory - Tinubu has also portrayed the protest movement as the work of unpatriotic agitators: “Capitalising on the economic hardship in the country, some men and women with sinister motives have been reported to have been mobilising citizens, particularly youths, to stage a protest.” As civilian leaders veer between conciliation and condemnation, the military has struck a more aggressive tone, warning that “the armed forces will not watch and allow the nation to spiral out of control to such low levels.”

Interestingly, in the states, some governors are trying to show empathy. Oyo State Governor Seyi Makinde called on protesters to remain peaceful, but also said, “We could be experiencing anger and hunger in the land and that is why our people want to protest.” Makinde’s tone, however, likely also owes something to the fact that he hails from the People’s Democratic Party (PDP), which is in the opposition at the national level. Indeed, one complicating factor for the protesters is that their movement has been accused of being simply a vehicle for the opposition, which has in turn generated accusations that Tinubu himself, who supported the Occupy Nigeria protest in 2012, is a hypocrite. You can read some statements from several opposition parties here, urging authorities to respect constitutional rights to free assembly and expression. At the state level, by my count 16 of the country’s 36 states are governed by the opposition (i.e., non-APC), and it will be interesting to see how those governors handle the protests.

One additional important debate concerning the protests is whether it is legitimate for Muslims to protest at all - a key debate worldwide, and one that has taken on added urgency in the wake of the Arab Spring protests in 2011. Some Muslim clerics and influencers argue that protests are illegitimate unless the religion is being directly suppressed, and that protesting is likely to cause chaos rather than solve problems. Such arguments often sit poorly with revolution-minded youth, who see protests as one of the few tools they have to get governments’ attention - and who see clerics as out of touch at best, or as paid agents of the powerful at worst. The clerics have already gotten some serious pushback over TikTok, Facebook, and other platforms, with fellow Muslims telling the clerics to stay in their lane and out of politics. In Nigeria, the clerics, especially in the north, face some serious credibility risks if the youth turn out en masse in clear defiance of their advice.

I think you could even extrapolate from the issue of the clerics to a question of whether Nigeria faces a generalized crisis of institutions. Some Nigerians might say the country is well past that - that from the presidency to the police to the pulpit, all major institutions already face a credibility gap and a problem of capture by narrow interests. But the protests may mark a new stage in widening that gap even further, as many ordinary people’s disgust with institutions and their managers becomes clearer and louder.

I do not know how big the protests will be or how many of their goals the protesters will achieve. The 2012 protests played a big role in delaying - although not preventing - the eventual removal of the fuel subsidy, and the 2020 protests made a huge impact and creating a long-lasting political memory but without fundamentally altering how the security forces relate to the civilian population. Inflation, meanwhile, is proving tremendously difficult for Tinubu to rein in. The protests in Kenya, meanwhile, are clearly rocking the authority of President William Ruto. In short, the protests - even before they occur! - have grabbed Tinubu’s attention and that of the nation, and in that sense they already constitute a major event. Whether they produce serious and structural change is another question; indeed, how to achieve such change is a problem that protesters and reformers around the world continue to grapple with. If nothing else, 2024 seems likely to join 2012 and 2020 as a key date in Nigeria’s protest history.