Shari'a Enforcement and Ramadan in Kano, Nigeria

Why has shari'a implementation in 21st-century northern Nigeria focused so heavily on regulating public life?

The BBC’s Mansur Abubakar:

The Islamic police in the northern Nigerian state of Kano have arrested Muslims seen eating and drinking publicly, as well as those selling food at the start of Ramadan, when Muslims are supposed to fast from dawn until dusk.

[…]

Last year, those arrested for not fasting were freed after promising to fast, while the relatives or guardians of some of them were summoned and ordered to monitor them to make sure they fast.

Those arrested this year were not so lucky as they will have to face the court.

Ramadan began in most parts of the Muslim world, including Nigeria, on the evening of February 28/March 1. (There is sometimes slight divergence over the start and end dates of Ramadan depending on the calculation methods different Muslim communities use to determine the start and end of lunar months.)

During Ramadan, Muslims are enjoined to refrain from food, drink, and sex between dawn and sunset. There are, however, exceptions mentioned directly in the Qur’an and exceptions that Islamic jurists have derived from the source-texts of Islam. There are also some differences of opinion about some details. In general, Islamic jurists interpret the source-texts to mean that the shari’a forbids the very sick person and the frail person and the menstruating woman from fasting. The jurists typically further hold that certain other individuals - such as the traveler and the pregnant or nursing woman - may choose not to fast, especially in the case of the pregnant woman if she fears that the fast could harm her fetus.

The BBC and other press coverage does not go into detail about whether and how the Islamic police (Hisbah Board) determined if any of those arrested had any of these exemptions. Nor has the Hisbah Board, from what I’ve seen, gone into great detail on social media. Their Facebook page was hacked last year and remains hacked. Their top official, Shaykh Aminu Daurawa (who has been the Hisbah’s commander on and off since 2011), has addressed other matters on his own Facebook page (including, notably, fasting rules for diabetics and those with ulcers).

If one can’t tell, merely by looking, whether someone is flagrantly breaking fasting rules or has a valid excuse, why would the Hisbah conduct mass arrests?

I can think of two main answers:

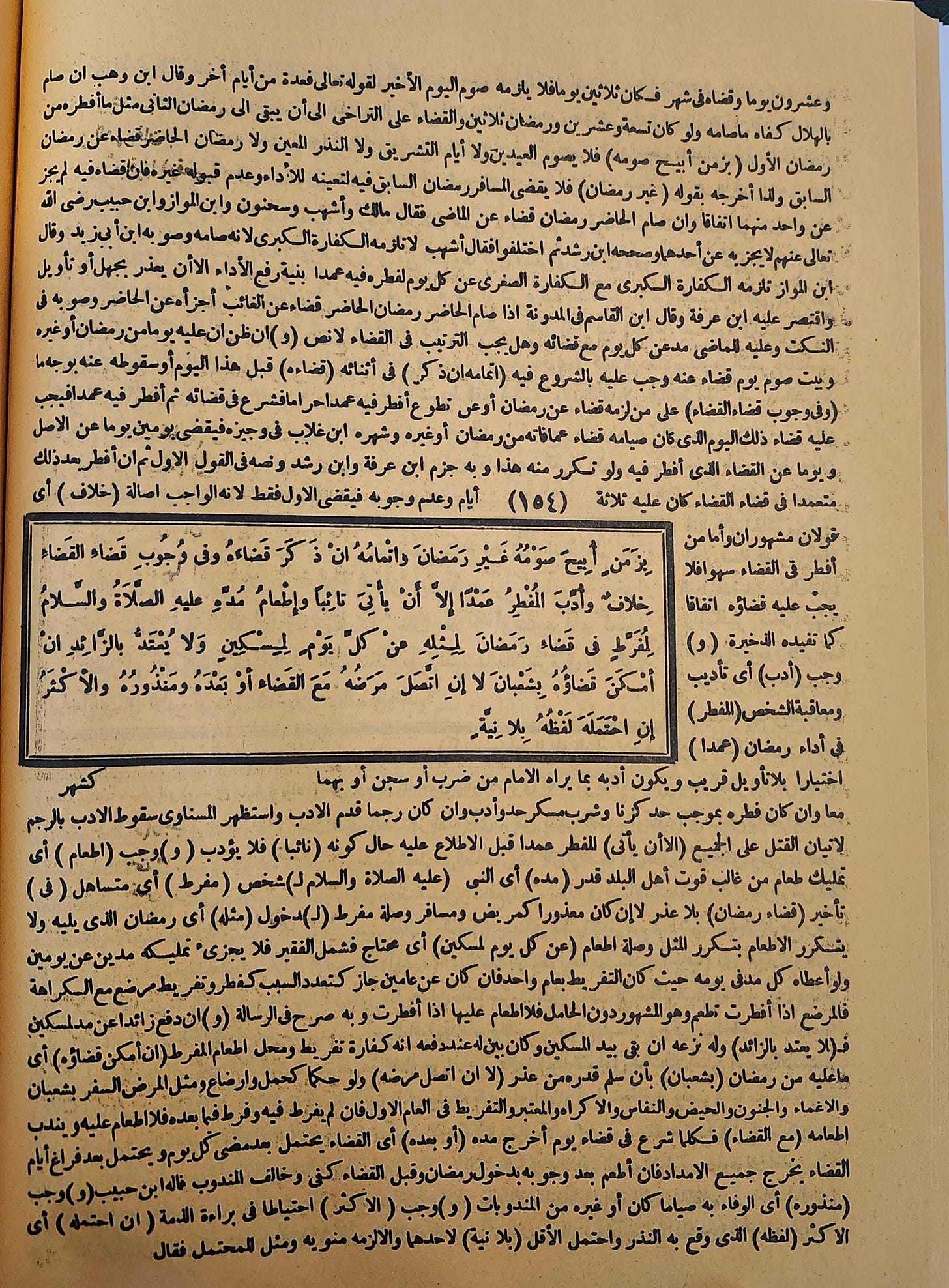

The first, trying to capture the internal logic of the Hisbah’s actions, is that classical Islamic legal manuals do enjoin punishment for those who deliberately break the fast without an excuse. The Mukhtasar (Abridgment) of Khalil bin Ishaq, for example, a widely influential legal text in northwest Africa, says “the one who breaks the fast deliberately is punished,” albeit without going into much detail (the Mukhtasar is notoriously terse); one commentary I have on my shelf, Jawahir al-Iklil (The Jewels of the Crown), adds that the punishment is discretionary, and should be “by what the Imam deems appropriate, whether a beating, imprisonment, or both” (Vol. 1, p. 154). The deliberate breaking of the Ramadan fast is seen as a heinous sin - although, notably, the Hisbah here does not seem interested in challenging the faith of the detained, which would open up a whole host of other issues pertaining to apostasy. In northern Nigeria as elsewhere, apostasy and blasphemy cases can become tremendously explosive. The Hisbah thus seems to be channeling the classical legal manuals in administering a punishment as a deterrent while not leaping to charges of apostasy.

The second answer, looking at things a bit more from the outside (although I don’t think these two answers are mutually exclusive), is that the “shari’a project” in northern Nigeria since 1999 has expressed itself through public displays of power and piety (for those interested in a deep dive on shari’a in twenty-first-century Nigeria, the books of Profs. Weimann, Kendhammer, and Eltantawi will take you far). The historian and anthropologist Prof. Murray Last has a very compelling article arguing that the restoration/expansion of shari’a in northern states rested partly on a “search for security” and a desire “to recreate a stronger sense of the ‘core North’ as dar al-Islam, with notionally ‘closed’ boundaries.” His explanation takes us a long way, I think, towards understanding why there has been such a focus, amid northern Nigeria’s effort at shari’a implementation, on these public efforts - separating the genders in public transportation, smashing the alcohol at bars and taverns, and, interestingly, holding mass weddings for widows and divorcées. Under the logic of shari’a as a search for security and closure, public eating in Ramadan is not merely an individual act but a threat to a particular vision of public order. One could imagine a different style of enforcement that focused more on, for example, regulation of market transactions or more individualized criminal investigations or a more passive stance where courts simply wait for petitioners to come to them. But the shari’a project is meant by its human architects in northern Nigeria to be seen and felt in the public arena, although levels and types of enforcement have fluctuated a lot over the past quarter-century. Kano is, in many ways, the ultimate laboratory in northern Nigeria for what shari’a enforcement and implementation means, given that the Hisbah there has been the most organized and most active in comparison to other states.

The criticism or alternative perspective on shari‘a among some northern Muslims, captured very well in Kendhammer’s book, is the idea that shari’a was intended to rectify society by deterring the corruption and abuses of those at the top. For those who held out that hope, the shari’a project has been a disappointment. Another strand of criticism has been that it is not always so easy to demarcate, even for pious Muslims, where the jurisdiction of something like the Hisbah begins and ends; one argument in play in the controversial trials of Safiyatu Husseini and Amina Lawal in the early 2000s, both of whom were ultimately acquitted on charges of adultery, was whether their initial arrests had violated Qur’anic prohibitions on spying into people’s private affairs (see Qur’an 49:12). Where public order ends and private affairs begin is a thorny issue for any legal system.

Trying to look at this year’s arrests from within the logics of northern Nigerian Muslim society and the shari’a more broadly, then, the arrests could represent (1) a defense of the integrity of a Muslim society (for backers of the Hisbah), (2) a serious overreach by the Hisbah (for cautious-minded traditionalists worried that careful procedures might not have been followed), or (3) a confirmation that the shari’a project targets the vulnerable while ignoring the powerful (for critics).

From the outside, of course, many observers will see these arrests as serious violations of religious liberties and human rights. But I think it’s important to consider the internal logics of the enforcement as well as various non-liberal criticisms that might be made; at stake here is not just a simplistic binary of “human rights versus shari’a,” but also contending interpretations of what shari’a is.