Who Is Shaykh Mabruk Zayd al-Khayr, the New Head of Algeria's High Islamic Council?

The elevation of a major Maliki scholar sheds light on how Algeria's religious establishment works.

One area of research for me is the present-day trajectory of the Maliki school, one of Sunni Islam’s four main legal schools. The Maliki school has long been followed in northwest Africa (and a few other places, such as parts of the Gulf).

To varying extents and in different ways, all of the North African states from Mauritania to Libya have empowered Maliki scholars within state-run Islamic affairs councils and fatwa bodies (a fatwa is a legal opinion or edict based upon a reading of Islamic source-texts and scholarship). Such councils have, especially in Morocco, been counterweights to the influence of Salafism in the society, and Morocco has advanced a quadruple framework - chérifien in monarchy, Maliki in law, Ash’ari in theology, and Sufi in spirituality - as a narrative of Moroccan Islamic identity and as an alternative to Salafism. In the Sahel, there are also Islamic affairs councils (see here for one treatment of these bodies), although those councils are more coded along Sufi versus Salafi lines than along Maliki versus Salafi lines.

Here it’s important to note that Salafism is at its core a theological movement (so saying “Ash’aris versus Salafis” makes the most sense here, if we’re talking binaries) but Salafis have also taken extensive aim at the traditional legal schools such as Malikism (meaning that we can also to some extent talk about “Malikis versus Salafis,” although there has also been substantial blurring of Malikism and Salafism in North Africa in recent years).

In North Africa, the Islamic Affairs councils and fatwa bodies do not have ultimate legislative authority. But they are, at a minimum, platforms from which prominent figures can intervene in important debates - whether as supporters of the state, or as independent voices. The most outspoken and controversial figure in this space is Libya’s al-Sadiq al-Gharyani (b. 1942), who is of course not even universally recognized as Grand Mufti (senior Islamic edict-giver) by all Libyans, given the political-military fragmentation there. Other top muftis and Islamic council heads can make news and reach wide audiences as well.

Algeria, following presidential elections in September, recently appointed a prominent and widely respected Maliki scholar, Shaykh (Dr.) Mabruk Zayd al-Khayr, as head of the country’s High Islamic Council. He succeeds Bouabdallah Ghlamallah (b. 1934), who had served as head of the Council since 2016 and who was previously the longtime Minister of Religious Affairs and Endowments (1997-2014). Ghlamallah’s website can be found here.

As is clear from the appointment session, Algeria has a dense web of senior religious positions - in addition to the High Islamic Council, there is a Ministry of Religious Affairs and Endowments as well as a presidential advisor on “religious affairs, Sufi lodges, and Qur’anic schools.” Morocco, though, I would say, has the most expansive state religious infrastructure out of the North African countries.

Born in 1961, Zayd al-Khayr is from Laghouat, a provincial capital and Saharan town some 400 kilometers south of Algeria’s capital Algiers. In terms of his academic training, his degrees are in language and linguistics, but with a heavily Islamic emphasis; his doctorate, obtained jointly from the Universities of Algiers and Cairo in 2010, looked at a linguistics concept I had to look up in English (!) called “predication,” and how this appears in terms of rhetoric and grammar in the Qur’an. Professionally, Zayd al-Khayr has held governmental and academic positions, sometimes simultaneously. For example, he became head of the Department of Islamic Studies at the University of Laghouat in 2010, and then added a position as director of the National Center for Research in Islamic Sciences and Civilization in 2015. A quasi-official biography of the shaykh can be found here.

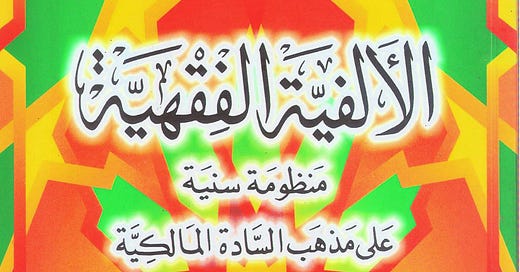

Of the shaykh’s writings, the one I have come across in my research is his 1998 poem describing Maliki rulings, called Al-Alfiyya al-Fiqhiyya: Manzuma Sunniyya ‘ala Madhhab al-Sada al-Malikiyya (The One-Thousand-Line Poem on Islamic Jurisprudence: A Sunni Versified Treatise Based on the School of the Maliki Masters). The text was graced with introductions and endorsements from numerous prominent shaykhs and academics. They included Shaykh Muhammad Bay Bilalim (1930-2009), one of the most famous Algerian shaykhs and Maliki jurists of the twentieth century, and Abderrahmane Chibane (1918-2011), who was Minister of Religious Affairs from 1980-1986. At a political level, these endorsements signaled that from a young age, Zayd al-Khayr was a rising star within Maliki circles and within Algeria’s religious establishment.

Many of the shaykh’s later writings deal with other topics, including language, literature, and linguistics. He continued, however, to lecture prolifically on Maliki jurisprudence, and he returned to his poem with his 2006 book Talkhis al-Fawa’id wa-Tajmi’ al-Fara’id (Summarizing the Benefits and Gathering the Gems), an extended commentary on his Alfiyya. Commentary (sharh) is a core genre in Islamic scholarly writing, and prose commentaries upon verse can be particularly helpful in explicating the poetry’s meanings. An example of the shaykh’s lectures on Maliki thought would be his series on the Muwatta’ (The Well-Trodden Path), the most famous work of Imam Malik bin Anas (d. 795), the founder/eponym of the Maliki school.

What do I make of the shaykh’s appointment to head the High Islamic Council, then? I take it as a sign of continuity albeit also as a generational shift. It’s also an example of how the figures appointed to such councils are not mere state functionaries but also scholars with serious profiles. Zayd al-Khayr’s appointment also confirms something I’ve been observing in the far different context of Libya, while doing some research on the professional backgrounds of senior shaykhs in that country - namely, universities are a key employer for rising shayhs, who also (like Zayd al-Khayr) tend to build multifaceted professional profiles as they teach in the classroom, lecture in mosques, and serve on national and international commissions. Retracing the career of Zayd al-Khayr, the religious establishment of Algeria appears to be a smoothly functioning machine, one that secures the buy-in of major scholars. That machine is also successfully reproducing itself, providing a path for younger scholars to build their individual reputations while also advancing their careers.

I don’t want to fall into a narrow kind of instrumentalism here - something I’ve had to think about a lot in my writing on how shaykhs navigate politics. From within Islam and from without, state-aligned scholars are sometimes dismissed as mere ulama al-sultan, pet scholars of the sultan. By referring to a “machine,” I don’t mean to suggest that everyone in it is a careerist - or that they function as robots. In fact, there’s been interesting research on the ways that religious bureaucracies can show independence and push back against executive dictates. There’s an implicit tension, even, between having an Islamic affairs council or a fatwa body but then running other parts of the state in a more or less secular way…and secularism itself has been described as a zone of perpetual ambiguity. A lot is at stake, then, in an appointment to such a senior post, including for that individual scholar, for the scholars as a class, and for the state and its strategies of legitimation.